First-Generation Immigrant Perspective on Black Lives Matter

Black Lives Matter Is More Than a Movement to Me — It's a Powerful Self-Affirmation

I've only seen my mother cry twice, but both times rocked my soul. The first time was when she received the news that her father died. My family was forced to flee from Liberia at the brink of the first Liberian Civil War in 1989, and we didn't have the means to leave all at once. The plan was to send for my grandfather once we were settled in the United States, but life had other plans.

The second time was when I walked into our kitchen, back-to-school shopping list in hand, and found her sitting at the table in tears. After a 120-hour workweek between both of my parents, they still couldn't make ends meet, and it was too much for her to bear.

When I think about the weight of the Black experience in this country, I'm reminded of my mother at the kitchen table and of all the moments where I was taught to internalize the message that my life and experiences didn't matter. My parents graduated from the University of Liberia, had good jobs, and were building a nice life before the years of unrest that led to the war. But in America, their African degrees did not carry the same value. So my mom worked 16-hour shifts for more than 25 years at nursing homes. My dad started a small business, which also required long hours. They didn't have time to dwell on the inequities they faced. Often they summoned superhuman strength to overcome challenges and fought much harder for a piece of the American Dream.

Despite these systemic hardships, my parents made sure that we grew up with a lot of love, joy, and faith in our household. My aunts, uncles, and cousins were always around, and there was always a Liberian dish like cassava leaf or palava sauce in the pot, a wedding to attend, or a family gathering in our home where my cousins and I would perform.

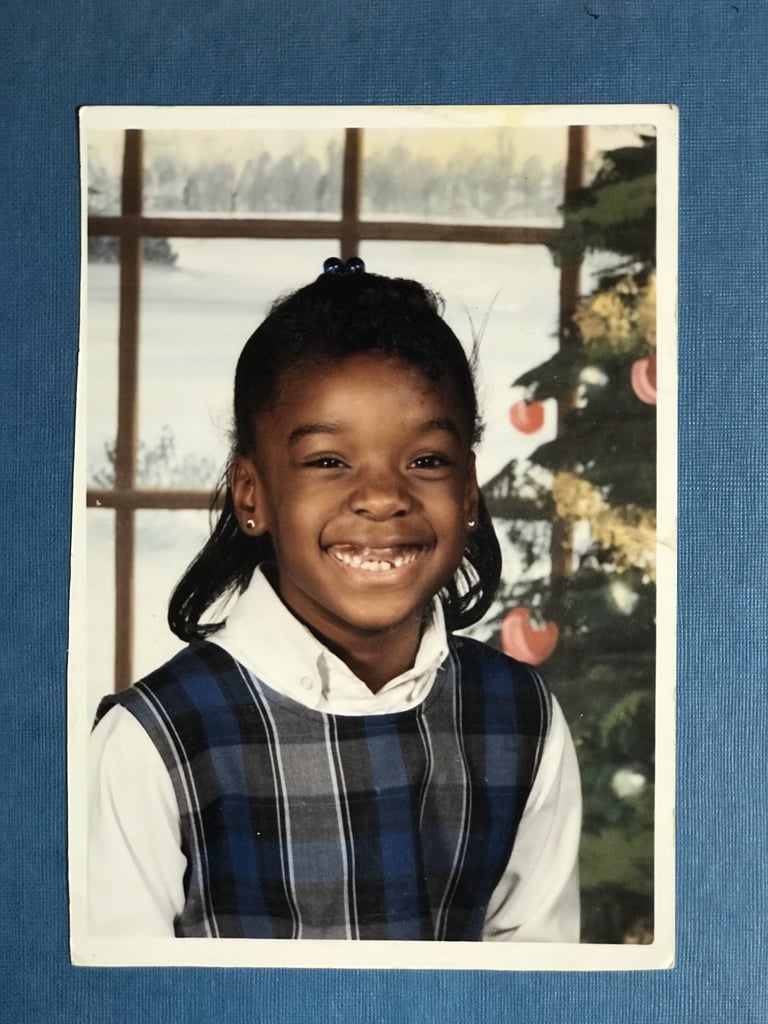

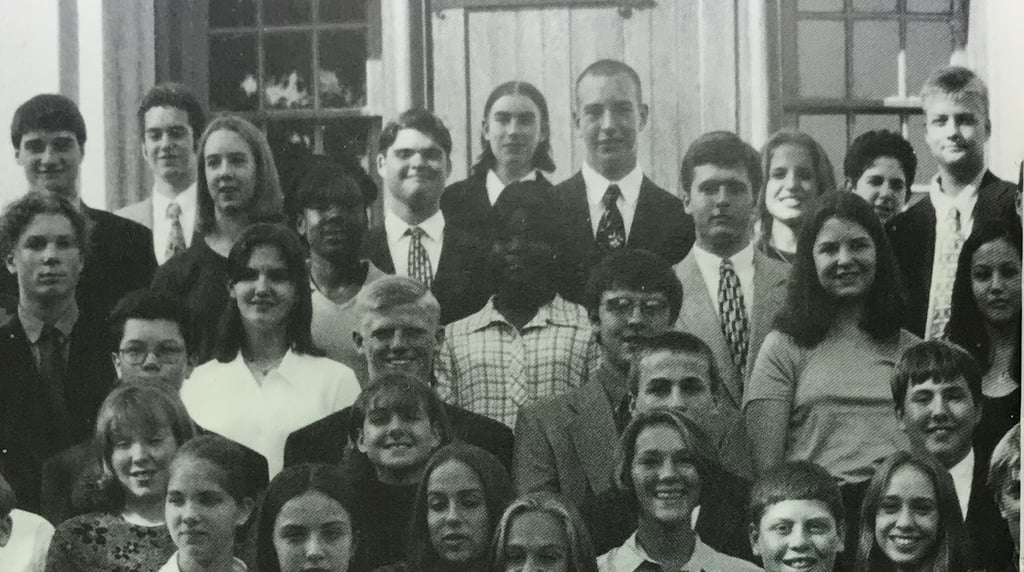

My parents saw education as a clear path for us to achieve our dreams. Although I took school seriously, the Newark, NJ, public school I attended was a challenging learning environment. Some families were experiencing poverty and hunger, some parents were abusive, some students were drug dealers, and some of my friends had brothers in jail. I was spit on, punched in the face, and sometimes bullied by both students and teachers. When I was in seventh grade, a representative from an organization called The Wight Foundation visited my school. They told us about their program and how they gave inner-city youth the opportunity to attend the best private boarding schools in the country, and I jumped at the chance. My parents were ecstatic when I got my acceptance letter to receive a scholarship to attend Blair Academy. However, I was low-key devastated because I realized that while public school was tough, I didn't want to leave my friends, family, and community. Nevertheless, even at age 13, I understood that very few Black kids had access to higher education. So I braced myself and cried all the way to boarding school.

When I got into NYU, I looked forward to living in New York City. Its diverse population would be refreshing. I found that everyone in the small community of Black students at NYU had unique Black experiences, but we all understood what it felt like to be one of the few students of color in classes. We understood the pressure and responsibility that came with getting through the university's doors. For us, there was no room for mistakes. So when I ran into a personal challenge, my GPA dropped and I lost one of my educational scholarships, I had to take periodic breaks from school to work full-time so that I could save for tuition. It took me a total of seven years and about $100,000 in student loans to get my BS in media, culture, and communication.

I believed that a degree from NYU and living in one of the most diverse cities in the world would make for a seamless transition into a career in the film and entertainment industry. However, when I walked into major media companies and found offices almost void of people of color, I realized that even with my scholarships and my education in prestigious white institutions, I still could not get in the door. I was only getting offers from low-paying jobs outside of my industry. This would make it nearly impossible for me to pay off my student loans before I was 60. Like my mother at the kitchen table, I felt defeated. I understood then that it would be nearly impossible for me, as a Black woman, to take a traditional route to a leadership position in the media and entertainment industry. I decided to forge my own path.

Part of me feels a lot of fear and anxiety in this moment of turmoil and transformation. In the name of peace and progress, it feels like Black people are being asked to be superhuman again. To quickly move past our pain, push down our anger, and be grateful that the white world has finally comprehended the impact of racial injustice on Black lives and minds. I am afraid that I will wake up tomorrow and this moment will be over without any long-term changes. Will violence against Black people by police officers ever stop? Will domestic policies that advance Black communities in America be actualized? Will companies transform the faces of their workforces? Will higher institutions be more accessible to students of color? Will Hollywood hire Black voices to tell the story of this moment?

The larger part of me is full of hope. Seeing the world collectively raise its voice to protest against racism makes me feel, for the first time ever, that we are all in this together. For me, Black Lives Matter is so much more than a statement of support for the Black community and our struggles. It has become a powerful self-affirmation. The statement and the movement have helped to psychologically reverse the messages I've received throughout my life that I mattered less than my white counterparts.

My hope for this moment is that the senseless murders of our Black brothers and sisters by police, the weight endured and sacrifices made by our ancestors and parents, and the current global protests will not be in vain. Let this be the moment where we work together to build a world where being treated equally (and feeling equal) is the status quo — and where none of us sit at the kitchen table and weep for what could have been.